I've invited anyone living with an invisible illness to share their stories here. This is Heidi's story about living with TYPE 1 Diabetes. Some of you may be shocked to see how serious this condition can be, I know I was.

When Pat asked if I would contribute my story to his blog, my first thought was, “Of course!” because I would do whatever I could to help him. Then I thought, “But my story isn’t that bad. I don’t want people to think I am comparing what I deal with to what Pat is dealing with”.

And I don’t. But as Pat said, few people do.

And my husband reassured me—what I do isn’t easy. And maybe if I tell my story, people will realize Type I diabetes isn’t just what they see me do (check blood sugar, take insulin, eat). There really isn’t a minute of any day that it doesn’t hover in the back of my mind, part of every decision I make about food, activity, and schedule for the day. Can I go to bed now? Do I need to eat first? Should I treat this high, or is it coming down on its own? Can I take a walk after supper without dropping low? Should I take my insulin before or after I eat this meal? Is it too hot outside for me to carry my insulin in my purse without an icepack? Do I have enough snacks or sugar with me to cover whatever it is we are planning?

…I am not invisible. Of course, people see me; I go to work, I teach little kids, I do the groceries, I walk down the street. A lot of the time, I am smiling and making jokes. Living life. Looking like everything is fine.

But what is going on inside me IS invisible. So much so that you’d probably never believe it even if I told you while I was suffering. I tend to make jokes and act casual to hide what’s happening with most everyone except those who are the very closest to me. I’m really good at hiding.

But let’s start at the beginning.

I have Type I diabetes and have since 1985 when I was 14 years old.

That summer, in 1985, I did not feel like myself. I was tired. I think I was depressed. I had a few weird experiences that I didn’t understand at the time, but I believe they were due to my pancreas kicking in and out at odd times, wreaking havoc. I was thirsty—the thirst was indescribable. It was all I could think about. When school started, I would have to go to the water fountain frequently. My French teacher asked if I couldn’t wait. "No," I said. "I really can’t." She suggested I might be diabetic—I agreed with her.

I kind of knew I might be.

I was eating SO MUCH and yet still losing weight. I mean, I was eating 2 or 3 servings at every meal. I was losing weight fast. To a teen girl, that didn’t seem like the end of the world. Sadly, I saw it as a blessing. But my weight just kept dropping. I knew something was wrong.

My mother took me to the doctor—more than once. I had blood tests. They always came back negative for diabetes. The doctor asked me if I was throwing up my food. “No, I said. Of course not.” He didn’t believe me because that’s what you say if you’re being diagnosed with anorexia or bulimia: “No! Of course I am not throwing up.” He prescribed these green pills, which they told me were food supplements, but it turns out they were Prozac. I didn’t need Prozac. Unfortunately, I experienced some of the less-common side effects—panic attacks, suicidal thoughts, and hallucinations. It was not a fun time. The green pills disappeared, and I don’t even remember when or why I stopped taking them. My friends helped me through more than one weird experience during this time—and (luckily) they always brought food. Popsicles, tea with sugar (lots—I was putting seven teaspoons of sugar in my tea at this point). I was starving to death and craving sugar all the time. My body couldn’t absorb any of the food I was eating because insulin is the key that opens the doors to our cells, so glucose (food energy) can get in. And I wasn’t making any insulin most of the time (pancreases die slow and jumpy deaths, it seems).

Finally, one of the tests they did came back positive (how could it not?).

But I still wasn’t sent to the hospital—just “Yep, it’s Type I diabetes.” The doctor must have sent the results to the Montreal Children’s Hospital. A few days later, THEY saw the numbers, and all hell broke loose. I was at school, dragging myself from class to class. My jeans were falling off. I weighed 88 pounds. I couldn’t catch my breath going up the stairs between classes. I smelled like Juicy Fruit gum; there was so much sugar in my blood. My blood sugar was around 38 mmol/l.

Normal is 4-6 mmol/l; a diabetes diagnosis usually comes in at 7 mmol/l for a fasting morning blood sugar.

I was driving full-speed toward a diabetic coma, and, you know, death.

I heard my name being called over the school intercom to come to the office. I went to see what was up, and they said to get my things; someone was coming to pick me up. Our neighbor was waiting for me in his car outside. I had no idea I wouldn’t be back for three weeks, or that at that point, it wasn’t sure I’d be back at all. I had no idea how sick I was.

I arrived home, and my mother handed me a bag she had shoved a bunch of my stuff into, and we headed to the hospital. They had told her not to let me fall asleep. I was tired, but I didn’t feel sleepy. My mother was terrified, and every time I blinked for too long, she would shout, “WAKE UP!”

I remember sitting on the E.R. exam table, and a doctor took one look at me and knew. No blood tests, nothing. He said he could smell it, and my breathing was so shallow he could see it—I was in ketoacidosis. Straight to the intensive care unit for me.

That was a long night. My mother had to go home to be with my younger brother. I was alone in the ICU. I didn’t know it at the time, but they told my mother I might not make it through the night. My mother never told me that; friends that she spoke to told me later.

I had IV’s all over the place, as my veins were hard to find, so I ended up with IV’s in the inside of one of my elbows, which was then strapped flat to a board, and believe it or not, the top of my foot. I had another line on the back of my hand, but I don’t think there was an IV attached; I think they used it as a port for injections.

Hospital nights are long. It’s a combination of quiet and noise, light and dark, that makes it hard to sleep. In the ICU, it’s never really dark because you are being observed. I drifted in and out of consciousness/sleep and looked out the window on the far side of the room. I thought I was looking at Mount Royal (maybe I was), and I thought that was where Corey Hart lived on Dr. Penfield (a street in Montreal). I don’t know if he really did, but thinking so kept my mind on other things. I sang the song Never Surrender to myself over and over that night—“Just a little more time is all we’re asking for….cause just a little more time can open closing doors…And when the night is cold and dark, you can see, you can see light! And no one can take away your right to fight and to never surrender-never surrender!” This song has been my mantra over the years.

I lived.

I learned how to inject insulin with a syringe and felt pretty cool when I drew the insulin into the needle and flicked it to get the air bubbles out like a doctor on TV. I learned how to measure my blood sugar, which in those days meant putting blood on a test strip and wiping it off carefully to compare the colour to the side of the strip bottle and try to make the best match you could. There have been highs and lows, literally and figuratively, as I tried to control my blood sugar.

I learned about food choices and how many servings I had to eat of what and at what time of day—with very little wiggle room. In the ’80s, an insulin regimen was very strict—insulins were not as precise or fast-acting as they are today, and long-acting insulin had peaks that meant you better eat your snack when you were supposed to, or you would regret it.

And an untreated low blood sugar can kill you, fast. I don’t think I understood fear until I felt what a very low blood sugar feels like.

I remember my very first low; I was still in the hospital. I must have been a little low at bedtime because the nurse brought in a styrofoam cup and said, if you wake up feeling weird, drink this. I woke up feeling very weird and remembered through my confused haze what she had said, so I drank it. I thought it was a medicine of some kind, but it turned out to be orange juice. I couldn’t even taste it.

During low blood sugars, I have had convulsions, lost my vision (more than once), lost the ability to speak coherently, and if I can still move around to take care of myself (because sometimes I can’t), I have very little control over what I eat. The urge to get carbs is unstoppable—my brain is taking over to save my body. I sweat so much it soaks through my pyjamas and the sheets, my heart rate goes haywire (and I can feel it), and have trouble catching my breath. And there’s a feeling of panic that makes everything even harder to deal with. You’re dying fast, and you know it.

These lows (which can happen even if I have done everything right) are terrifying. They’ve changed me permanently. I developed an anxiety disorder, which was probably part of my nature anyway, but in large part was due to the fear that something I did or didn’t do could kill me at any given moment.

They told me in the hospital when I was fourteen that I would be cured in ten years. They are still telling new diabetic kids that; I read it on message boards and blogs all the time. I wasn’t too worried about complications because teens are invincible, and I believed I would be cured soon. Thirty-five years later, I am still diabetic. I do have complications, even though I take good care of myself.

I have developed a frozen shoulder. It is most common in females aged 40-60, and type I diabetics (10-20% of us get frozen shoulder, according to Web MD). I knew about frozen shoulder, but it always sounded so benign. "So you can’t move…eh." Well, let me tell you, it hurts. During the freezing stage, a false move like a cough, sneeze, or bumping into a doorway causes a sharp, brutal, all-encompassing blast of white-hot pain. It recedes slowly, but in the meantime, you’re doubled over sobbing like a maniac. You can’t just grit your teeth and bear it; it’s an unstoppable reaction. I was in that painful pre-freeze stage for 12 months and in the frozen stage for 18 months. Fully frozen, it was duller but more constant. My range of motion was limited (non-existent, according to the orthopedic surgeon I saw). Nothing to be done—the only possible help were cortisone injections and hyrdodilation that might work. This is where you have saline and cortisone injected into your shoulder joint to forcibly try and open the joint up using the pressure of the liquid being injected and cortisone to help with the pain. The doctor said it might hurt. It did hurt. A lot. I could definitely feel the joint opening up. I’m sure the people in the waiting room knew it hurt, too. Ahem.

The injections didn’t work for me in the end. The first one gave me a few days of relief (instead of the hoped-for 4-6 weeks) and the second didn’t do anything at all. My doctor said not to bother with the third. Surgery doesn’t help, so I just had to live with it, trying to do stretches to help keep what motion I had. I did physio for eight months, and it didn’t help. Acupuncture and osteopathy didn’t help, either. I’m coming out of the final stage slowly; it’s been another 12 months or so. I have a lot of my range of motion back, but my arm is still stiff and barks at me loudly if I move it too far.

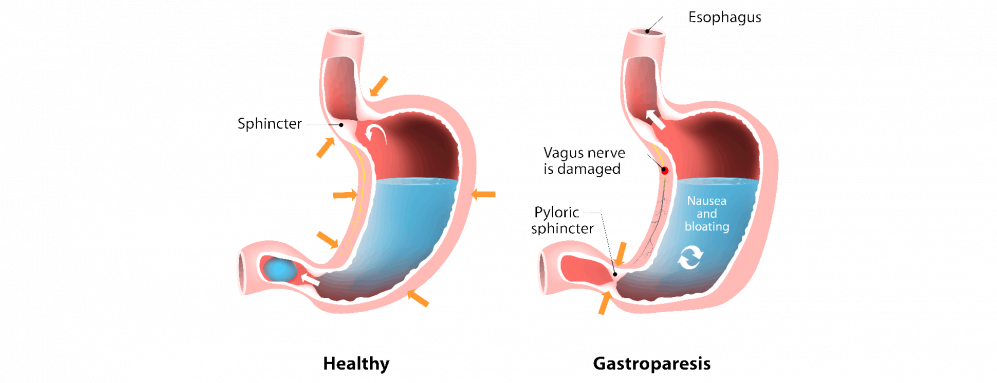

I also have gastroparesis, which recently has been the hardest thing to deal with. This is a paralysis of the digestive system caused by damage to the vagus nerve, which controls the contractions that move food through our systems. This is NOT FUN when you are taking insulin to lower your blood sugar because you aren’t digesting your food (so your blood sugar isn’t going up). Food sits in your stomach, useless until it spontaneously decides it’s moving along. If I go low when this is happening, treating is hard—because anything I eat or drink will also sit there.

Lately, I eat, and my food doesn’t start moving through my gut for 4-5 hours. I can’t take my insulin with my meal like I am supposed to, because when I do (and did before I learned my lesson), my blood sugar drops low very quickly, insulin searching to remove sugar from my blood that hasn’t arrived yet because it is still in my stomach. Even though I try to combat it with glucose tablets—nothing is getting through my gut, so it takes a long time to rise, which is extraordinarily dangerous—it can be fatal. My wonderful husband, daughter, and dear friends have sat with me while I wait for my blood sugar to come up, glucagon injection at the ready in case I pass out, phone ready to call 911. Glucagon is a hormone that will raise blood sugar levels, meant to be used if you fall unconscious.

In light of this, I now take my insulin when I see the food has started being digested. I wear a flash glucose monitor in my arm and use a handheld device so I can see it in just about real-time. No more putting blood on a strip and waiting for the colour to change! This post-meal wait means I have to let my blood sugar go high before I treat it and then wait longer than usual for it to come down. Ideally, diabetics try to avoid spikes in their blood sugar in order to avoid complications (retinopathy, kidney disease, heart disease, nerve damage, and many more). Not an easy fix and not the best way to manage diabetes at all. But for safety’s sake, it will have to do.

The harder part is the nausea, bloating, and fullness. When things are bad, it feels like I have had a load of concrete poured down my throat every time I eat. I don’t even want to eat during a flare. But I have to because I have to take insulin, or I will die. And I can’t take insulin without eating.

The worst flare I had was ten days long. For the first few days, I could hardly eat at all. I was drinking Gatorade and meal replacement drinks. I was trying to walk to get things moving, but I had no energy, and it felt like I was dragging myself. I was getting 500-600 calories a day at best.

My healthcare team has been great, even though not much is known about gastroparesis. The dietitian helped me learn what foods I should be avoiding, and they are all the foods you’d think would be healthy to eat—salads, legumes, nuts, seeds, raw vegetables, most fruits. Anything with a lot of fiber, if it takes too long to digest, it’s out. This is really hard for people to understand and accept—those foods are all supposed to be healthy and AID digestion, so why can’t I eat them?

And here’s the crux—maybe the hardest part—people argue with me about MY health and tell me why what my doctors are telling me to do is wrong. Most people only have a rudimentary understanding of diabetes at best, and when you combine it with a problem like gastroparesis, it becomes a very complicated animal. Why on Earth would people think they can armchair quarterback this one? It is frustrating and demoralizing to have to argue with people, so most often, I don’t.

I try to remember they think they are helping, and they care.

I also want to say that for the most part living with type 1 diabetes is very manageable. If I am careful, most things work out. There are always curveballs, but I have learned how to deal with most of them. I am very aware of my health and am conscientious about taking care of myself. A lot of the time, I AM smiling because I AM happy.

I just wish people knew. How hard it all is—how much planning and thinking and effort goes into my daily activities. How terrifying a low blood sugar episode can be is and why I worry about them so much. How after thirty-five years of experience, I can still be surprised by a low or a high that technically shouldn’t have happened because I DID EVERYTHING I WAS SUPPOSED TO DO.

I know I’m not invisible. But do you really see ME?

Heidi

Never Surrender – Corey Hart

Just a little more time is all we're asking for'Cause just a little more time could open closing doors

Just a little uncertainty can bring you down

And nobody wants to know you now

And nobody wants to show you how

So if you're lost and on your own

You can never surrender

And if your path won't lead you home

You can never surrender

And when the night is cold and dark

You can see, you can see light

'Cause no one can take away your right

To fight and to never surrender

With a little perseverance

You can get things done

Without the blind adherence

That has conquered some

And nobody wants to know you now

And nobody wants to show you how

So if you're lost and on your own

You can never surrender

And if your path won't lead you home

You can never surrender

And when the night is cold and dark

You can see, you can see light

'Cause no one can take away your right

To fight and to never surrender

To never surrender

And when the night is cold and dark

You can see, you can see light

No one can take away your right

To fight and to never surrender

To never surrender

Oh, time is all we're asking for

To never surrender

Oh, oh, you can never surrender

The time is all you're asking for

Ooh, stand your ground, never surrender

Oh, I said

You never surrender, oh

Susan T.

Wow. It isn't as if I didn't know a lot of the issues you deal with, Heidi... But the way you expressed them really drove it all home and because you show such strength outwardly I do often forget how every decision is tied up with your health and can be life or death results. The worse part is doing everything you are supposed to and it still goes awry. Thank you for sharing ❤

Nathalie C.

Thank you for sharing Heidi's story Pat. Type 1 diabetes has always been something I have dread! It is such a treacherous disease!!! I also have "invisible friends" battling it, and I the hardships of this condition. I will pray for Heidi, that she continues to do well fighthing this condition and that she never surrenders!!! Be well, be safe Pat.